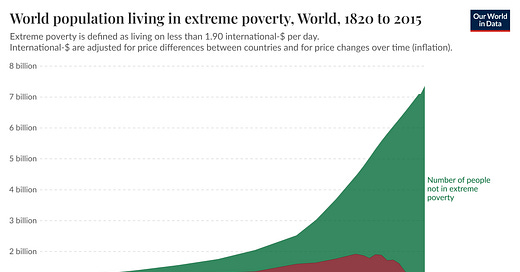

In the past 30 years, the most severe poverty on Earth fell. A lot. The details are subject to debate, and there are those (most prominently Jason Hickel), who deny the core claim.1 But in general, it’s close to consensus.

If you ask why, answers tend to come in out-of-breath staccato, as everyone rushes to yoke their cart to a particularly gorgeous horse. Free market guys say it’s free markets. China fans say it’s China (and indeed, quite a lot of it is China). Or perhaps it’s decolonization, technological development, or globalization.

A recent paper by Armentano, Niehaus, and Vogl is not interested in why poverty fell, on a big picture level. And indeed, most mature takes on the issue admit that there are many interrelated reasons. Instead, they study how poverty fell. Which is to say, what did it look like for individual households in countries that saw large moves out of poverty? What were the typical mechanisms by which a family in Indonesia went from being desperately poor to getting by? Was it receiving government subsidies? Moving to a city? Working in a more lucrative industry?

This post will explore that paper’s high level conclusions, for a lay audience. If you want to know how people got way less poor during the last 30 years in a handful of pivotal countries, it’s your lucky day.

Housekeeping

First, let’s get methodology out of the way. Armentano et al confined their study to five countries: China, India, Indonesia, South Africa, and Mexico. This is for two reasons:

70% of extreme poverty reduction happened in these countries, and

they had good, longitudinal studies to rely on for data.

Their threshold for extreme poverty is “$2.15 per day in 2017 PPP dollars”, meaning, what $2.15 could buy you in 2017. This is the standard throughout papers on the subject, and (to reiterate) is adjusted for inflation. To level set, the eye-popping global reduction is “44% in 1981 to 9% in 2019”.

Two central questions the paper explores are churn and cohorts. Churn is moving back and forth over the (extreme) poverty line; high churn would be everybody being poor some years and well off other years, and low churn would be a permanent, hopeless underclass. Cohorts are groups of people clustered by age, like “Millennials” but narrower. Within-cohort change is the same group of people getting richer as they age, and between-cohort change is poor grandparents having well-off grandchildren.

Finally, the paper followed both consumption - i.e. how much households spent2 - and income, depending on which was available in their data.3

Central Findings

Narratives about poverty often emphasize the way that it’s a trap, with little hope of escape. While this rings true for many (see, for instance, best-picture winning film Parasite)4, the global story is different.

Using income-based measures, the probability of exiting poverty conditional on starting in it ranged from 26% in South Africa to as high as 57% in Rural India. But the probability of entering poverty conditional on starting out non-poor was also substantial, ranging from 15% in South Africa to as high as 34% in Mexico. Estimates using consumption, where they are available, tell the same basic story. Transition probabilities generally appear flat or—in the case of China and India—shift advantageously over time. Overall, the global picture is one in which poverty falls at a moderate pace not primarily because individual households remain stuck in it, but because the rate at which they exit it is moderately above the rate at which others fall back into it.

In other words, churn was high in all the countries studied, with fortunes changing frequently. Rather than a steady titration pulling people from the lower class to safety, people were whirling back and forth between social classes all the time, just up more often than down.

What about cohorts?

We confirm that as poverty has fallen in aggregate, successive birth cohorts have entered adulthood at progressively lower poverty rates. However, we also find that the pace of this between-cohort process roughly matches the within-cohort pace of poverty decline. Poverty rates are similar across the age distribution at a point in time; aggregate poverty decline manifests in downward parallel shifts of a flat cross-sectional age profile. This fact holds true whether we use consumption or income, where available, as well as whether we focus on household heads, as is common practice, or take all household members into account.

In other words, new generations were less poor than old ones at the same age, but also people got less poor as they aged. So narratives about dynamic youths flooding to opportunity while their grandparents withered aren’t quite right, nor were crotchety Baby Boomers hoarding all the wealth. People just kind of got richer over time, full stop. (Except, remember, some of them got poorer.)

Pathways

So far, we have a picture of poor parts of the world becoming more dynamic, with fortunes rapidly changing but overall, people of all ages being financially buoyant. Now, let’s look slightly closer. How would a typical person (or family) change their fortunes?

This is one of the most interesting parts of the paper. There are many narratives you may be familiar with, if you’ve ever thought about the topic. They’re basically all wrong.

For almost all countries and dimensions of activity, only a minority of the households that exited poverty did so while changing their primary means of earning a living.

Most people who escaped poverty kept doing the same kind of work, rather than pursuing more lucrative industries. Continuing the same quotation:

And households that entered poverty often changed their activities in ways similar to those that exited. For example, the share of poverty-entering households that switched from agriculture to non-agriculture is 53%-114% the corresponding share of poverty-exiting households.

There are lots of stories about microloan recipients going into a new line of work, or poor subsistence farmers striking it rich in the city. But in fact, switching to a new career is risky business, and can make you poorer just about as easily as richer.

Speaking of “striking it rich in the city”:

Migration, particularly rural-to-urban migration, also accounts for a limited amount of poverty decline in the three countries (Mexico, Indonesia and South Africa) for which migrants were tracked, with the one notable exception that rural-to-rural migrants accounted for a third of all net poverty decline in Indonesia.

This seems (to me) to be pushing back against the idea that urbanization is the silver bullet to eradicate poverty, at least in middle-income nations. Not only did lots of people get richer staying in the same line of work, they also got richer staying put (or, for Indonesians, moving somewhere no denser).

So we’ve established that lots and lots of poverty reduction involved people not making big changes. Did any kind of change predict upward mobility? Yes, but it varied between the countries under study:

With respect to occupational choice, patterns are quite different in the more developed economies (Mexico and South Africa) relative to the less developed ones (China, India and Indonesia). In the former group, transitions within and into wage work account for the bulk of poverty decline, while in the latter, those who stayed or became self-employed contributed the most.

The authors suppose that steady jobs are best in the somewhat richer and better organized economies of Mexico and South Africa, while when there’s a dearth of steady jobs in general, self employment is the way to go. Of course, it might make sense to discount any finding that’s not consistent across all the countries in the study; 5 countries is a lot more than 3, or 2, for drawing cross-cultural conclusions.

You might be wondering if cash transfers - redistribution, foreign aid, or remittances - were centrally important. Nope:

We also see no cases in which changes in transfers (from public and private sources) played a dominant role. Among households that exited poverty, the share of income they obtained from transfers either rose slightly or fell substantially. Among those that entered poverty, the share generally rose substantially or fell slightly. Overall, the data are consistent with progressive redistribution, but not with transfer income accounting directly for a major share of the income gains that moved households above the poverty line. In this sense, the households that left poverty did so largely on their own.

Inspiring! This does suggest that redistribution helped households that fell into poverty (notice that households falling into poverty had a greater share of help), but it was never a huge factor in aggregate.

Last but not least, it’s everyone’s favorite topic, female labor force participation:

Finally, poverty transitions have a nuanced relationship with women’s participation in the labor force. In most countries, households in which a woman entered the labor force contributed meaningfully to poverty decline, while those in which a woman exited the labor force experienced either an increase in poverty or at best a lower-than-average decrease. These patterns are consistent with the mechanical contributions to household living standards that one would expect from having an additional income earner. China is the exception. In China, households in which a woman began working exited poverty at the highest rate of any group, but they were greatly outnumbered by households in which a woman left the labor force, which accounted for nearly half of all net poverty decline. This result suggests a stronger selection effect in China than elsewhere, wherein women withdrew from the labor force when their households could afford it.

So, Chinese households valued having women out of the labor force a lot, and many Chinese women stopped working once the society around them got rich enough to allow this. Though everywhere, including China, women entering the labor force made a big decrease in poverty when it happened. Checks out.

Data Details

So far, all my quotations have come from the introduction, which summarizes the paper’s findings in somewhat more detail than the abstract or conclusion. While I did read the denser methodological sections (and do think the paper itself is well worth reading), I won’t go into much detail on them. But I will share some interesting tidbits.

On global policies that likely drove the macro level:

In terms of the policy environment, the data span several episodes of economic liberalization. These include India’s relaxation of a wide range of economic regulations starting in 1991; ongoing market-oriented reforms in China during the 1990s such as the passage of the first Company Law in 1993 and a push towards privatizing state-owned enterprises in 1998-2000; the ratification of the North American Free Trade Agreement (directly affecting Mexico) in 1994; and China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. South Africa, meanwhile, undertook wide-ranging reforms focused on increasing equity following the end of apartheid in 1994. These included, for example, land redistribution under the Restitution of Land Rights Act of 1994, labor market reform via the Labor Relations Act of 1995, and policies to promote black business ownership. Overall, the data overlap with some of the most significant episodes of policy reform in recent history, at least as concerns poverty reduction.

Interesting that India/China liberalized, Mexico/China got much better trade opportunities, and South Africa’s state apparatus underwent active redistribution after apartheid. No singular solution!

On whether there was a core of ultra-disadvantaged people who had little to no hope of escaping poverty:

Another potential nuance is that the basic story—that households in poverty had a high probability of exiting it—may have been less true for some than for others. Some may have had more opportunity to make progress, while others were truly stuck. Because the panels extend over several rounds, we can examine this issue: if it were true, we would see the conditional probability of escaping poverty tending to fall over time, as more and more of those capable of exiting would have already done so.

So basically, if some households were “truly stuck”, they’d make a higher proportion of the impoverished over time, and so positive churn would decrease. But in fact, the relevant probabilities stayed flat, or grew more advantageous over time. So probably, during the time period studied, there was not much of a “destitute core”.

On the patchwork nature of the whole thing:

First, no one pathway out of poverty predominates. Only a minority of households that exited poverty did so while changing their status on any one of the margins we examine—sector, occupation, location, or female labor force participation.5

Conclusion

If I had to summarize one thing I took away from this paper, it was that huge reductions in deep poverty are dynamic. Small-scale cash transfers in extremely poor areas are a noble pursuit, but our most salient examples of income growth are a fundamentally different thing. Rather than imagining programs pulling people out of poverty traps, the biggest reductions come from huge explosions of social and economic change, which build some people up and knock others down. Of course, “have a gigantic change to the socioeconomic reality of your country” is not exactly a policy prescription, and my guess is that most such changes have turned out horribly.

Maybe the takeaway is just gratitude. There’s no law of reality that said material conditions had to improve for thirty years straight, for gigantic swathes of the Earth’s population, for varied reasons. It just happened!

May it happen again.

Okay, not exactly. Consumption also includes the value of gifts received, stuff the household makes for themselves, and a small grab bag of other non-monetary stuff. But spending is a decent approximation.

You might think income would be the gold standard, but consumption has its advantages. For example, it helps address income shocks; very poor households might make very different amounts of money year over year, but will smooth out their consumption to a more stable level to survive leaner periods.

Happy Oscars weekend, mom!

They do note China is an exception here, with female labor force participation actually explaining 55%, but that case is weird since it’s more like a consequence (richer household lets woman stop working) than a cause (woman enters labor force, household income skyrockets).

I think this discussion would be much richer if it accounted for what else was going on in these economies at the same time i.e rapid economic growth. That makes it possible for your productivity to rise even if you are doing the same thing. Your time is worth more because other people's time is worth more!